Happy Sunday {{first_name|friend}}!

This is part three out of three in a series about the implications of AI for work. Part One was Labor and Part Two was Enterprise. You don’t really have to read either one before this one but in my head they flow together!

Usually in these posts I aim to do my own writing. But this week, I want to share a long excerpt from this piece by Ethan Mollick because it is one of the most thought provoking frameworks I’ve encountered so far about what AI can mean for work. I read it a few weeks ago and still feel like I am processing the implications.

Here’s the relevant parts with some mild edits, and then I’ll add another couple thoughts at the end. If you want to read the original piece first, definitely go do that and then come back here.

One of my favorite academic papers about organizations is by Ruthanne Huising, and it tells the story of teams that were assigned to create process maps of their company, tracing what the organization actually did, from raw materials to finished goods. As they created this map, they realized how much of the work seemed strange and unplanned. They discovered entire processes that produced outputs nobody used, weird semi-official pathways to getting things done, and repeated duplication of efforts. Many of the employees working on the map, once rising stars of the company, became disillusioned.

I’ll let Prof. Huising explain what happened next: “Some held out hope that one or two people at the top knew of these design and operation issues; however, they were often disabused of this optimism. For example, a manager walked the CEO through the map, presenting him with a view he had never seen before and illustrating for him the lack of design and the disconnect between strategy and operations. The CEO, after being walked through the map, sat down, put his head on the table, and said, "This is even more fucked up than I imagined." The CEO revealed that not only was the operation of his organization out of his control but that his grasp on it was imaginary.”

For many people, this may not be a surprise. One thing you learn studying (or working in) organizations is that they are all actually a bit of a mess. In fact, one classic organizational theory is actually called the Garbage Can Model. This views organizations as chaotic "garbage cans" where problems, solutions, and decision-makers are dumped in together, and decisions often happen when these elements collide randomly, rather than through a fully rational process. Of course, it is easy to take this view too far - organizations do have structures, decision-makers, and processes that actually matter. It is just that these structures often evolved and were negotiated among people, rather than being carefully designed and well-recorded.

The Garbage Can represents a world where unwritten rules, bespoke knowledge, and complex and undocumented processes are critical. It is this situation that makes AI adoption in organizations difficult, because even though 43% of American workers have used AI at work, they are mostly doing it in informal ways, solving their own work problems. Scaling AI across the enterprise is hard because traditional automation requires clear rules and defined processes; the very things Garbage Can organizations lack. To address the more general issues of AI and work requires careful building of AI-powered systems for specific use cases, mapping out the real processes and making tools to solve the issues that are discovered.

This is a hard, slow process that suggests enterprise AI adoption will take time. At least, that's how it looks if we assume AI needs to understand our organizations the way we do. But AI researchers have learned something important about these sorts of assumptions.

Computer scientist Richard Sutton introduced the concept of the Bitter Lesson in an influential 2019 essay where he pointed out a pattern in AI research. Time and again, AI researchers trying to solve a difficult problem, like beating humans in chess, turned to elegant solutions, studying opening moves, positional evaluations, tactical patterns, and endgame databases. Programmers encoded centuries of chess wisdom in hand-crafted software: control the center, develop pieces early, king safety matters, passed pawns are valuable, and so on. Deep Blue, the first chess computer to beat the world’s best human, used some chess knowledge, but combined that with the brute force of being able to search 200 million positions a second. In 2017, Google released AlphaZero, which could beat humans not just in chess but also in shogi and go, and it did it with no prior knowledge of these games at all. Instead, the AI model trained against itself, playing the games until it learned them. All of the elegant knowledge of chess was irrelevant, pure brute force computing combined with generalized approaches to machine learning, was enough to beat them. And that is the Bitter Lesson — encoding human understanding into an AI tends to be worse than just letting the AI figure out how to solve the problem, and adding enough computing power until it can do it better than any human.

The lesson is bitter because it means that our human understanding of problems built from a lifetime of experience is not that important in solving a problem with AI. Decades of researchers' careful work encoding human expertise was ultimately less effective than just throwing more computation at the problem. We are soon going to see whether the Bitter Lesson applies widely to the world of work.

…The Bitter Lesson suggests we might soon ignore how companies produce outputs and focus only on the outputs themselves. Define what a good sales report or customer interaction looks like, then train AI to produce it. The AI will find its own paths through the organizational chaos; paths that might be more efficient, if more opaque, than the semi-official routes humans evolved. In a world where the Bitter Lesson holds, the despair of the CEO with his head on the table is misplaced. Instead of untangling every broken process, he just needs to define success and let AI navigate the mess. In fact, Bitter Lesson might actually be sweet: all those undocumented workflows and informal networks that pervade organizations might not matter. What matters is knowing good output when you see it.

I bolded that last line for you friends who just skimmed that whole italics bit and arrived here. Here’s my TLDR takeaway:

In the era of humans and AI working together, the most important role we humans can play is defining what success means to us.

But here’s the thing…we often kind of suck at doing that! Go into any random business and ask ten people what success means at that company and you are likely to get ten different answers. It’s quite hard for teams to maintain a SHARED and CLEAR definition of “good output” across their work and over time.

For organizations to truly incorporate AI into their business, the first step is not “let’s teach it how we do it so it can do it faster.” The first step is going to have to involve the humans determining and articulating a shared and clear definition of success in a way they might not have ever done before.

Figuring that out as a team is going to be really cool. And hard. And important.

Those conversations alone might just make the whole AI project worthwhile.

Ask your team members this week…

If we hired a robot and it asked you how it knows if it is doing a good job, what would you tell it?

Assorted announcements

I’m doing a webinar with Amilia and the JCC Denver team on Tuesday - come if you want to learn more about our work with setting up Salesforce for the JCC and building our integration with Amilia.

I’ll be at Colorado Startup Week on Wednesday and Thursday - if you’re there let me know!

We’re considering building software for synagogues…might be insane but might be very cool. If you have any interest in this topic, let me know here? Interest, ideas, tips, people to talk to, strong warnings to stay far far away…I want to hear it all.

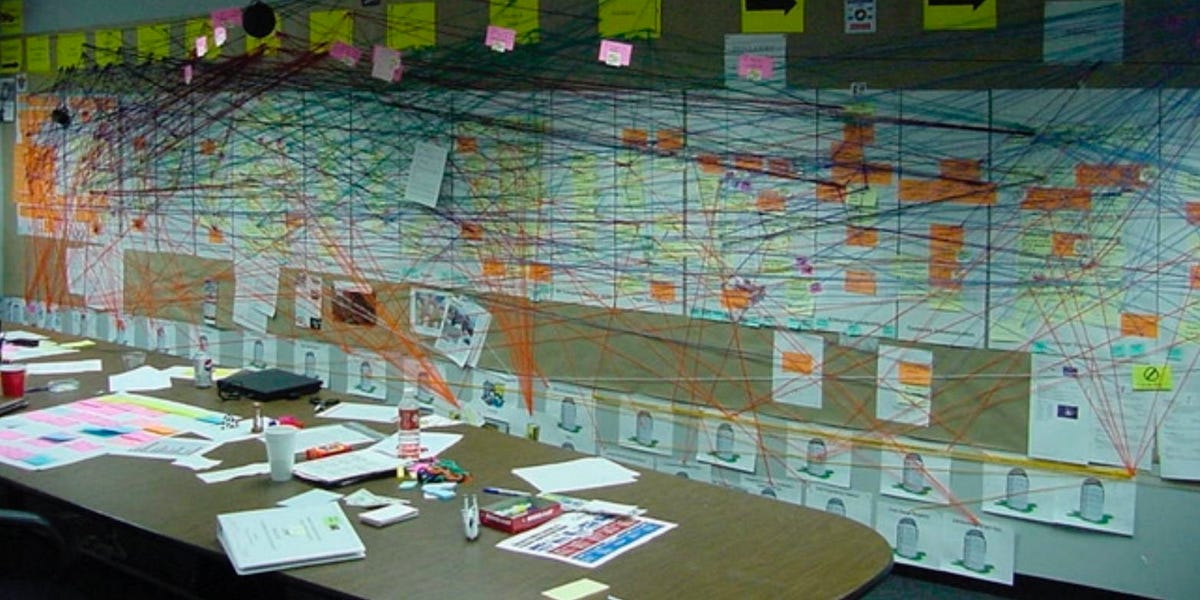

Irrelevant photo I just wanted to include because it is cool and there weren’t any other photos in this post

Saw a rain shower in the sun when I was landing in Denver last Wednesday!